Blak Douglas’ sun-splashed studio in Redfern is a sight to behold. The walls are covered with his works and even the stairs have been painted the colours of the Aboriginal flag. “You know what I’ve just realised? We’ve made a historic discovery. iPhones don’t recognize the word ‘lamingtons’,” he says, reaching into a paper bag mid-interview to pull one out. “How un-Australian,” he announces, then laughs.

Blak is a Koori artist with Dhunghutti ancestors, who works primarily in the medium of acrylics on canvas. His compositions bring light to the contemporary concerns of racism in postcolonial countries, critically interrogating through his own language how it feels to be embroiled within the Commonwealth of Australia as an Aboriginal person. “I do believe that part of becoming a so-called citizen of this ‘great nation’, you must sit with an Aboriginal activist. Everybody needs to do it. It doesn’t matter where you come from. I’ve dealt with African refugees and refugees from the Middle East, and they will blind you with a fanfare of Australiana, of the Australian spirit,” he says. “When you become a citizen, you get a brown bag with an Australian flag made in China, a little wattle branch, a koala pin for your lapel … That’s all BS. You need to sit and listen to an activist, and the activist will tell you that in theory, it’s no different to where you’re coming from.”

His new exhibition Transparent Covenant is held at JEFA Gallery in Bangalow and it is his first large solo in six years. Blak describes his art as being “conveyed through parody, irony and truth”, each work often revealing several layers of scathing political commentary.

Deride and Conquer

Synthetic Polymer on Canvas

65cm x 60cm

Blak’s approach is sardonic and satirical, at times combining witty turns-of-phrases with scraps of everyday life to raise awareness; other times delivering hard-hitting polemic against hegemonic structures. “The main thing that fuels my desire to get up and create in the genre of Aboriginal art, if it can be pigeonholed as a genre, is that we are constantly at war. And we’ve been in battle for 229 years now. If my art or my imagery could spark a revolution, that would be what I hope to achieve before I go to my grave.”

Certain writers have referred to my work as ‘Aboriginal hip hop on canvas’, and I think it’s perfect … Hip hop can be a rhythmical sucker punch. You don’t see it coming but then it just hits you, even if you’ve enjoyed getting to that point where you get hit. That’s what my work does.

“The show details my typically quirky take on the ironies of existing as a survivor of the genocide inflicted upon my Dhunghutti ancestors by successive ‘Australian’ Governments.” His compositions bring light to the contemporary concerns of racism in postcolonial countries, critically interrogating through his own language how it feels to be embroiled within the Commonwealth of Australia as an Aboriginal person. Ultimately, he is concerned with opening up modern dialogue on white colonialism, a history that remains painfully recent and relevant for him.

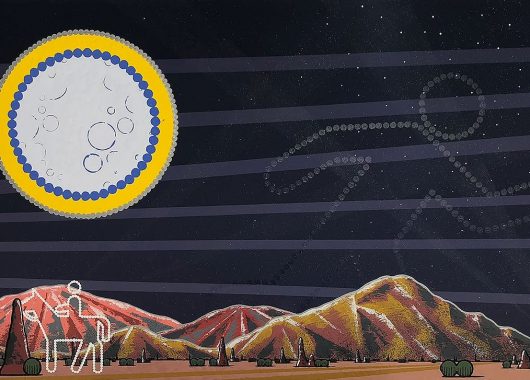

One Night the Coon

Synthetic Polymer on Canvas

100cm x 150cm

When asked about what it’s like to navigate the art world as an Aboriginal artist, he says: “The experience of being in the Archibald is an important note to be taken because the art galleries and major institutions in Australia are effectively funded by offspring of people that were the perpetrators of the original genocide on Aboriginal people. It’s like dining with Henry VIII. Even if you’re the nominal performer or the artist, meaning you get to entertain him while he gets drunk or eats his roast, you’re very well likely to have your head put under the guillotine after dinner. That’s what it’s like being an Aboriginal artist.”